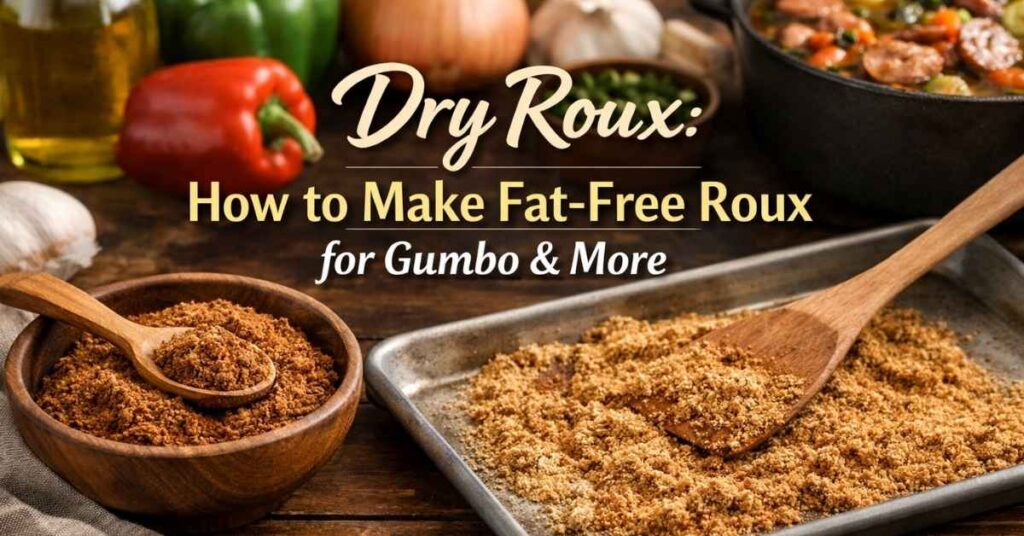

Dry roux is one of those quiet kitchen techniques that looks simple on the surface but delivers deep flavor, control, and flexibility once you understand it. If you love Cajun or Creole food, cook gumbo regularly, or simply want a lower-fat way to thicken soups and stews, dry roux deserves a permanent place in your cooking routine.

Unlike a traditional roux made with oil or butter, dry roux is created by toasting flour on its own. No fat. No splattering. Just flour, heat, and patience. The result is a nutty, aromatic thickening agent that adds color and flavor without heaviness.

In this guide, you’ll learn what dry roux is, where it comes from, how to make it using different methods, how to use it correctly, and when it works better (or worse) than a traditional roux. Everything is explained in a simple, easy-to-read way, with practical tips you can actually use in the kitchen.

What Is Dry Roux?

Dry roux is flour that has been browned without oil or fat. As the flour heats, it slowly changes color and develops a toasted, nutty flavor. When added to liquid, it still thickens, though slightly less aggressively than a fat-based roux.

Many cooks also call it toasted flour roux or oil-free roux. Despite the lack of fat, this roux plays the same functional role as traditional roux: it thickens and flavors dishes like gumbo, soups, stews, gravies, and sauces.

What makes this roux special is its balance. You get deep flavor, more control, and easier storage, all without extra oil or butter.

Where Dry Roux Comes From: Cultural and Historical Context

This roux has strong roots in Cajun cooking, where efficiency and flavor have always mattered. In traditional Southern kitchens, cooks often made roux in large batches. Over time, many discovered that browning flour on its own was faster, safer, and easier to store.

In rural Cajun homes, this roux was commonly used for gumbo when oil was scarce or when cooks wanted to prepare ingredients ahead of time. While not every classic recipe uses it, this roux is widely accepted as authentic and traditional, especially in home cooking.

As one Louisiana cook once put it:

“Dry roux lets you build flavor before the pot ever hits the stove.”

That mindset still applies today.

Dry Roux vs Traditional Roux

Understanding the difference helps you choose the right tool for the job.

| Feature | Dry Roux | Traditional Roux |

| Fat content | None | Butter, oil, or animal fat |

| Flavor profile | Toasted, nutty | Rich, buttery |

| Thickening power | Moderate | Strong |

| Ease of storage | Excellent | Limited |

| Risk of burning | Lower | Higher |

| Best uses | Gumbo, soups, stews | Creamy sauces, gravies |

This roux is ideal for brothy dishes, while traditional roux shines in rich sauces where fat plays a starring role.

Why Cooks Choose it

This roux isn’t just a “health swap.” It offers real, practical advantages.

First, it allows for lower-fat cooking without sacrificing flavor. Second, it’s easier to batch and store, making weeknight cooking faster. Third, it reduces the risk of burns, since there’s no hot oil involved.

Many cooks also prefer this roux because it creates a cleaner, more controlled flavor base. You can adjust thickness separately from richness, which is harder to do with traditional roux.

Understanding This Roux, its Color and Flavor

Color matters more than many people realize. As flour browns, both flavor and thickening power change.

A light dry roux is pale tan with mild flavor and stronger thickening ability. It works well in lighter soups.

A medium dry roux, often described as peanut-butter colored, offers the best balance. This is the most common choice for gumbo.

A dark dry roux is deep brown with bold, nutty flavor but reduced thickening power. It’s best for hearty stews where flavor matters more than thickness.

The darker the roux, the less it thickens—but the more flavor it adds.

Ingredients and Tools You Need

Dry roux requires very little.

Most cooks use all-purpose flour, though whole wheat flour can add deeper flavor. Some gluten-free blends work, but results vary.

Tools matter more than ingredients. A baking sheet or heavy skillet, a whisk or spatula, and patience are the keys to success.

How to Make Dry Roux in the Oven

The oven method is the most forgiving and consistent.

Preheat your oven to 350°F. Spread flour evenly on a baking sheet. Place it in the oven and stir every 15 minutes. Depending on your desired color, the process takes 45 to 75 minutes.

You’ll know it’s ready when the flour smells nutty, looks evenly browned, and no longer smells raw. Let it cool completely before storing.

This method is ideal for batch dry roux and beginners.

How to Make Dry Roux on the Stovetop

The stovetop method is faster but requires attention.

Add flour to a dry skillet over medium heat. Stir constantly as the flour changes color. Remove it immediately once it reaches your desired shade.

This method works well for small batches but demands focus. Even a few seconds of neglect can lead to burning.

Can You Make Dry Roux in the Microwave?

Yes, but it’s less precise.

Microwave this roux involves heating flour in short intervals, stirring between each round. While convenient, browning is often uneven. Use this method only when necessary.

How to Use Correctly

Using this roux properly prevents lumps and uneven texture.

The key is gradual incorporation. Many cooks whisk this roux into cool liquid first, then add it to hot broth. Others sprinkle it slowly while stirring continuously.

This roux works best when added early in cooking, giving it time to hydrate and thicken evenly.

Best Dishes to Make with this Roux

This roux shines in dishes where flavor and structure matter.

It’s most famous in gumbo, but it also works beautifully in soups, stews, gravies, and sauces. Plant-based cooks especially appreciate it because it adds body without oil.

Because this roux stores well, it’s also perfect for meal prep cooking.

How Much to Use

Measurements depend on the dish.

A good starting point is one tablespoon per cup of liquid for light thickening. For thicker results, increase gradually.

Always adjust slowly. You can add more, but removing thickness is harder.

Read more>>>Dan Bongino Wife Accident: Facts, Rumors, and What We Know

Common Mistakes

Most problems come from rushing.

Uneven browning, burnt flour, and under-toasting are the most common issues. Stirring regularly and using moderate heat prevent nearly all mistakes.

Can You Fix Burnt Dry Roux?

Unfortunately, no. Burnt dry roux tastes bitter and cannot be saved. When in doubt, throw it out and start over. Flour is cheap. Flavor is not.

Storage, Shelf Life, and Make-Ahead Tips

This roux stores extremely well.

Once cooled, place it in an airtight container and keep it at room temperature. Properly stored dry roux can last several months without losing quality.

This makes it a perfect make-ahead ingredient for busy kitchens.

Is Dry Roux Healthier Than Traditional Roux?

This roux is not a diet food, but it is a lower-fat alternative. By removing oil or butter, you reduce calories and saturated fat while keeping flavor.

For many cooks, that balance makes dry roux a smart everyday option.

Can Dry Roux Replace Traditional Roux in Any Recipe?

This roux works best in liquid-based dishes. It may not fully replace traditional roux in creamy sauces where butter or oil provides richness and mouthfeel.

Knowing when to use each is the mark of a skilled cook.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is dry roux as flavorful as traditional roux?

Yes, but the flavor is toasted rather than buttery.

Can dry roux be made ahead of time?

Absolutely. It’s one of its biggest advantages.

What color dry roux is best for gumbo?

Medium to dark is most common.

Does dry roux clump?

Only if added too quickly or without stirring.

Final Thoughts:

This roux proves that simple techniques often deliver the biggest rewards. With just flour and heat, you can create depth, structure, and flavor that elevates everyday cooking.

Whether you’re making gumbo, soup, or gravy, mastering dry roux gives you more control, less stress, and better results. Once you try it, you may find yourself reaching for dry roux more often than traditional roux—and wondering why you didn’t start sooner.